OBOR - One Belt, One Road

News Mediarail.be

China > Freight > OBOR

> OBOR - Political context

> OBOR - The railway project

>> OBOR - Technique de transport, flux et points de transbordement

>> OBOR - Résultats, chiffres et commerce

> OBOR - The railway project

>> OBOR - Technique de transport, flux et points de transbordement

>> OBOR - Résultats, chiffres et commerce

The author:

Frédéric de Kemmeter

Railway signalling systems. I'm a rail observer for over 30 years. How has the railway evolved over the decades? Which futur for railways? That's what I'm analyzing and explaining.

Railway signalling systems. I'm a rail observer for over 30 years. How has the railway evolved over the decades? Which futur for railways? That's what I'm analyzing and explaining.

OBOR and geostrategy

After years of whirlwind economic development, China is seeing a bit of a slowing down in its growth.

Beijing is now looking beyond China's borders for opportunities to invest, trade and secure vital energy supplies, not to mention bolster the country's international standing. If there is one thing at which China’s leaders truly excel, it is the use of economic tools to advance their country’s geostrategic interests.

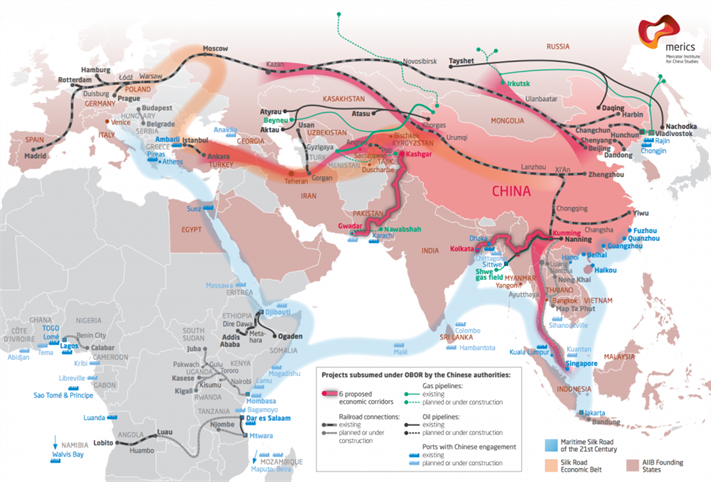

"Belt and Road" is a massive trade and infrastructure project that aims to link China — physically and financially — to dozens of economies across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Oceania. It consists of two parts: The "Belt," which recreates an old Silk Road land route, and the "Road," which is not actually a road, but a route through various oceans.

Behind the diplomatic language and the policy speak, what exactly is One Belt, One Road? OBOR has the potential to be probably the world’s largest platform for regional collaboration. As of January 2018, 71 countries (including China) are taking part in the project. They include India, Pakistan, Poland, Turkey, New Zealand, and Russia. Altogether, these 71 countries represent 4 billions people for a third of the world's GDP. It is a gigantic project that turns its back on the United States, which has been practicing an isolationist policy since the election of Donald Trump. So we immediately see the geopolitical strategy that China wants to lead, especially when Russia and Europe are concerned.

Beijing is now looking beyond China's borders for opportunities to invest, trade and secure vital energy supplies, not to mention bolster the country's international standing. If there is one thing at which China’s leaders truly excel, it is the use of economic tools to advance their country’s geostrategic interests.

"Belt and Road" is a massive trade and infrastructure project that aims to link China — physically and financially — to dozens of economies across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Oceania. It consists of two parts: The "Belt," which recreates an old Silk Road land route, and the "Road," which is not actually a road, but a route through various oceans.

Behind the diplomatic language and the policy speak, what exactly is One Belt, One Road? OBOR has the potential to be probably the world’s largest platform for regional collaboration. As of January 2018, 71 countries (including China) are taking part in the project. They include India, Pakistan, Poland, Turkey, New Zealand, and Russia. Altogether, these 71 countries represent 4 billions people for a third of the world's GDP. It is a gigantic project that turns its back on the United States, which has been practicing an isolationist policy since the election of Donald Trump. So we immediately see the geopolitical strategy that China wants to lead, especially when Russia and Europe are concerned.

See also:

• My photos on Piwigo gallery

• My YouTube channel

• My blog with latest news

• Follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn

• My photos on Piwigo gallery

• My YouTube channel

• My blog with latest news

• Follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn

For the purpose of funding this project, a bank named Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIT) has been established in China with a capital of one hundred billion dollars. Besides, China has formed forty billion dollar Silk Road Fund. Beijing is using government and non-governmental organizations to implement the plan.

In October 2013, President Xi Jinping presented his visionary plan to the world where China will be connected to Central Asia, South and Southeast Asia and Europe by land routes. China is also building oil pipelines along the routes. Those who know a little about geography know that a land route to reach Europe passes either through Russia or Iran and Turkey. The first road is a choice of stability, despite the Putin regime. The second route is a risky choice because it crosses regions under embargo (Iran) and close to conflict zones (Iraq, Syria). As OBOR develops, markets along its routes will open up and diversify. Barriers to trade will come down and business environments will become more conducive to overseas investment. Western firms offering consulting, management and other professional services will see demand for their services increase, while industrial sectors such as telecommunications, finance and energy will all require Western technology and expertise. These pages will focus more specifically on the OBOR rail project.

In October 2013, President Xi Jinping presented his visionary plan to the world where China will be connected to Central Asia, South and Southeast Asia and Europe by land routes. China is also building oil pipelines along the routes. Those who know a little about geography know that a land route to reach Europe passes either through Russia or Iran and Turkey. The first road is a choice of stability, despite the Putin regime. The second route is a risky choice because it crosses regions under embargo (Iran) and close to conflict zones (Iraq, Syria). As OBOR develops, markets along its routes will open up and diversify. Barriers to trade will come down and business environments will become more conducive to overseas investment. Western firms offering consulting, management and other professional services will see demand for their services increase, while industrial sectors such as telecommunications, finance and energy will all require Western technology and expertise. These pages will focus more specifically on the OBOR rail project.

Major export centers

While geostrategy plays the leading role, two other arguments are offered to connect China to Europe by land. First, the Chinese ports today have become giants who are already suffering from downstream traffic jams. On the other hand, China does not want to focus its growth solely on the coastal part of the country. The contrast is striking today between East and West, where the population remains very poor. In addition, the major production centers are located in the interior of the country, sometimes far from the coast. Encumbred access to ports increases the transfer time of goods and containers, sometimes more than 10 days in China. Then you have to count the customs procedures, the operations on the terminal and then only the loading on a ship, for a trip that can last from 25 to 35 days following the stops and the policy of 'slow steaming' (lower speed of the ships for decrease fuel consumption). All this makes the railway more attractive, despite two rail gauges and the route through Russia.

The map below shows China's main production centers:

The map below shows China's main production centers:

If we look at the where the highest frequencies of trans-Eurasian trains depart from in both China and Europe we often find massive high-tech industrial zones. These trains connect cities like Chongqing, Chengdu and Zhengzhou - the new arteries of the Chinese manufacturing world - with Duisburg, Hamburg or Rotterdam - the main industrial areas of Europe. We find in these chinese cities electronic components and heavy machinery of great value. These are products that customers often want to get to their destination as soon as possible and that are valuable. Goods that justify the higher price of rail transport, which halves the transit time between the factory and the consumer.

Dubbed the ‘city of the laptops’, Chongqing is home to leading global electronic brands and contract manufacturers and is reported to be the largest single PC production centre in the world. When a new rail option opened in 2011, HP began testing the viability of shipping finished goods overland 11,000km west to Germany, rather than sending them 1,700km east to the Chinese coast for long-dstance export by sea into Europe.

Dubbed the ‘city of the laptops’, Chongqing is home to leading global electronic brands and contract manufacturers and is reported to be the largest single PC production centre in the world. When a new rail option opened in 2011, HP began testing the viability of shipping finished goods overland 11,000km west to Germany, rather than sending them 1,700km east to the Chinese coast for long-dstance export by sea into Europe.

RUSSIA

MONGOLIA

CHINA

Yiwu, the world’s largest small commodities market, is where many $1 shops round the world get their products, from soft toys to balloons to imitation jewellery. It has over 200,000 shops catering for an equal number of visitors daily. Its floor space is equivalent to more than 1,000 football fields, and it is said that it could take more than a year to check out all the shops.

Capital of Sichuan Province, Chengdu is located in the economic belt of the Yangtze River, an essential element of China's free trade zone. The city has become the global center of the R & D industry in the telecommunications sector. The high tech industrial development zone is home to a large number of IT giants, as well as a large number of logistics companies.

These few examples are enough to show that China's power is not limited to Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Local authorities are heavily involved in industrial development.

These few examples are enough to show that China's power is not limited to Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Local authorities are heavily involved in industrial development.

The railway project

Drawing heavily on historical imagery of the old Silk Road that ran from China to Europe through Central Asia, OBOR envisions to create a land-based industrial belt to connect mainland China with Europe by rail.

In reality, this rail connection has existed for a long time. China has been connected by rail with Russia since 1961, thanks to the construction of the Trans-Mongolian railway which passes through Ulan-Bator and joins the famous Trans-Siberian Railway at Ulan-Ude, no far away of Lake Baikal. The gauge of the Chinese rail tracks is identical to that of Europe, 1,435mm. But in Mongolia and Russia, the choice was 1,520mm for all its network, including the Trans-Siberian, until to the Polish border. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, former Soviet republics, also have a railroad at the Russian gauge.

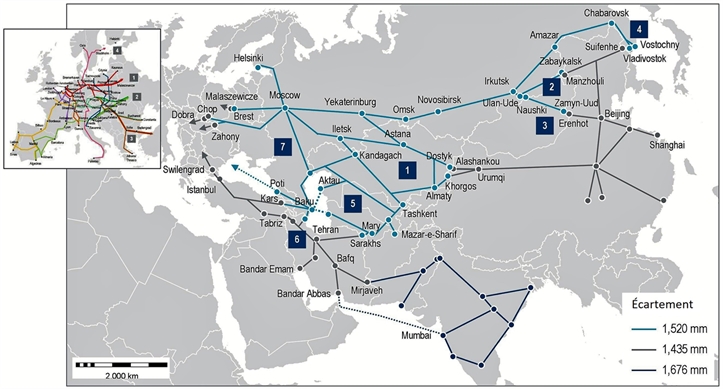

Currently, the favorite routes pass through Russia and Poland. We distinguish two main routes as shown in the map below:

In reality, this rail connection has existed for a long time. China has been connected by rail with Russia since 1961, thanks to the construction of the Trans-Mongolian railway which passes through Ulan-Bator and joins the famous Trans-Siberian Railway at Ulan-Ude, no far away of Lake Baikal. The gauge of the Chinese rail tracks is identical to that of Europe, 1,435mm. But in Mongolia and Russia, the choice was 1,520mm for all its network, including the Trans-Siberian, until to the Polish border. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, former Soviet republics, also have a railroad at the Russian gauge.

Currently, the favorite routes pass through Russia and Poland. We distinguish two main routes as shown in the map below:

- a road via Mongolia (in green)

- a road via Kazakhstan (in red)

A third road leads north of China. All these routes meet in Yekaterinburg and continue to Moscow, then Belarus and Poland. The route via Iran and Turkey is not on the agenda and is anyway not the shortest. According to Far East Land Bridge Ltd., the New Silk Road train journey also saves 75% of the carbon footprint of the ocean route while running only 11,000 km instead 22,000 km on the sea route.

A more detailed map of the UIC shows us seven possible routes by rail to reach Europe:

- a road via Kazakhstan (in red)

A third road leads north of China. All these routes meet in Yekaterinburg and continue to Moscow, then Belarus and Poland. The route via Iran and Turkey is not on the agenda and is anyway not the shortest. According to Far East Land Bridge Ltd., the New Silk Road train journey also saves 75% of the carbon footprint of the ocean route while running only 11,000 km instead 22,000 km on the sea route.

A more detailed map of the UIC shows us seven possible routes by rail to reach Europe:

Gauge

Details of the seven routes are showing in a UIC survey:

Routes

Length

Transit time

Comments

Alashankou /

Dostyk ou Khorgos

Dostyk ou Khorgos

> 10.000 km

> 14-17 jours *

> High reliability, good infrastructure

> Sufficientcapacities, new terminal in Khorgos

> Sufficientcapacities, new terminal in Khorgos

Manzhouli /

Zabaykalsk (RU)

Zabaykalsk (RU)

> 11.000 km

> 17-18 jours *

> High reliability, good infrastructure

> High volume, limited capacities in Zabaykalsk

> High volume, limited capacities in Zabaykalsk

Erenhot / Zamyn-

Uud (Mongolia)

Uud (Mongolia)

> 10.500 km

> 18-19 jours *

> Alternative to route 2

> weak infrastructures in Mongolia

> weak infrastructures in Mongolia

Suifenhe /

Vostochny (RU)

Vostochny (RU)

> 11.500 km

> 18-19 jours *

> High reliability, good infrastructure

> Suitable route to Korea

> Suitable route to Korea

Dostyk ou Khorgos

Baku

Baku

> 12.000 km

> 19-23 jours *

> Alternative for traffic to Southern Europe

> Limited capacity, 2 times RoRo shipping

> Limited capacity, 2 times RoRo shipping

Khorgos-Tashkent

Tehran / Turkey

Tehran / Turkey

> 12.500 km

> hardly used *

> Route as to be developed

> weak infrastructure and limited capacities

> weak infrastructure and limited capacities

> 13.500 km

> hardly used *

Tehran-Baku-

Moscow / Turkey

Moscow / Turkey

> Route as to be developed, weak infrastructure

> Suitable route for traffic from India to Europe

> Suitable route for traffic from India to Europe

* Transit time from a survey of 2012. Likely to improve over years.

Which goods ?

The New Silk Road train that is faster than marine transport and cheaper than air transport appeals especially to customers who have time-sensitive goods, such as merchandise to be sold as part of special promotions in the apparel industry or capital-intensive goods such as automotive parts or electronics. The surplus costs of rail transportation compared to the marine routes can be offset by the reduction in inventory costs and timely delivery. On average, the transit from China to Europe on the New Silk Road is about 14 to 18 days for blocktrains and 18 to 21 days for single container shipments.

After moving a large amount of their production from coastal Shenzhen to inland Chongqing, Hewlett-Packard found themselves in a logistical conundrum: will they ship their products east halfway across China to the coast just to ship them west again to Europe? Will they send everything via costly air freight? Or will they come up with a new solution? With the new Silk Road, HP stacks its computers into containers which are then loaded onto a train and send directly westwards. The containers are swapped in the inland terminals of Khorgos (Kazakstan) and Małaszewicze (Poland) to interconnect the railway systems of China, Russia and Western Europe.

After moving a large amount of their production from coastal Shenzhen to inland Chongqing, Hewlett-Packard found themselves in a logistical conundrum: will they ship their products east halfway across China to the coast just to ship them west again to Europe? Will they send everything via costly air freight? Or will they come up with a new solution? With the new Silk Road, HP stacks its computers into containers which are then loaded onto a train and send directly westwards. The containers are swapped in the inland terminals of Khorgos (Kazakstan) and Małaszewicze (Poland) to interconnect the railway systems of China, Russia and Western Europe.

Compared to ocean freight, the shipment process of the computers is significantly reduced, which increases the throughput rate, reduces the financing of stock and hence frees up cash for HP. As a result, the total cost of operations is impacted positively, which is why companies like HP have shifted to the rail. So goods travelling to Europe via the maritime route take a relatively long time to reach their destinations anywhere between 25 to 45 days. In contrast, a train from Chongqing (China) to Duisburg (Germany) can deliver the same goods in 14 days – half that time.

The climate, a challenge

We talk not here of the worldwide issue about global warming, but rather extreme conditions on the Trans-Siberian railway and in Kazakhstan. Products shipped by train along these routes are temperature sensitive, such as electronics or sophisticated machinery. Everyone knows that it is not advisable to ship computers when the temperature is negative by 40 ° C. The Silk Road holds a particularity: transporting smartphones, tablets and IT goods in ... refrigerated containers ! For this, another problem appeared: how to maintain the refrigerant motor for the entire time of the journey, knowing that there are no extra electrical outlets on the wagons? A thermostat-type solution has been found by the Dutch firm Unit45, to which we will return in more detail.

We talk not here of the worldwide issue about global warming, but rather extreme conditions on the Trans-Siberian railway and in Kazakhstan. Products shipped by train along these routes are temperature sensitive, such as electronics or sophisticated machinery. Everyone knows that it is not advisable to ship computers when the temperature is negative by 40 ° C. The Silk Road holds a particularity: transporting smartphones, tablets and IT goods in ... refrigerated containers ! For this, another problem appeared: how to maintain the refrigerant motor for the entire time of the journey, knowing that there are no extra electrical outlets on the wagons? A thermostat-type solution has been found by the Dutch firm Unit45, to which we will return in more detail.

No direct trains !

It is strongly recommended to take into account some technical evidences forgeted by the traditional media: there are no direct trains between China and Europe, but a chain of three distinct train services. At the operational level, we have five steps:

- The Chinese transit. Towards the West, the lines are not electrified and it is therefore large diesel locomotives that take over the traffic, which is not a good argument for the carbon footprint despite trains from 40 to 50 containers. The railway tracks have a gauge of 1.435mm. Some tracks have arrived with this gauge under the container cranes at the border points, for transhipment.

- 1st transhipment at the borders. Between China and Mongolia, Kazakhstan or Russia, the gauge of the rail passes from 1,435 to 1,520 mm. Given that transhipment of containers is easy, it is more efficient to unload containers from a chinese train to a kazakh train or a russian train. The other argument is ownership of wagons. Neither Russians nor Chinese want to trade them, many owned by private companies. Picture right: the new Khorgos terminal in Kazakhstan for China / Russia exchange

- Russian, Kazakh and Mongolian transits on 1,520mm tracks gauge. Since we do not change the bogies, given the ease of transhipment containers, they are changing trains. So there are never Chinese freight cars on Russian or Kazakh network, and the respective railways use their own rolling stock, RZD or KTZ. The route is on a non-electrified line, except for the approach of Moscow and Trans-Siberian, electrified in 25kV or 3kV according to sections. It will be like this through Belarus, as far as the Polish border, with several different locomotives.

- 2nd transhipment, after transit in Russia and Belarus (or Ukraine). It is carried out in Małaszewicze in Poland, which is becoming increasingly congested, and whose terminal is managed by PKP Cargo. The Russian 1,520mm track is present alongside European gauge tracks, 1,435mm. Here too, the owners prefer that their wagons stay on their respective network, because of this transhipment.

- The European final transit. It begins in Malaszewicze, Poland, after a second transhipment of containers on European wagons. For this third part of the trip, a variety of operators, whether private or public service, are used. The route ends near terminals, where a diesel locomotive makes the last kilometer to push trains under the container gantries.

Conclusion: No locomotives or Chinese wagons comes on European ground...

Conclusion: No locomotives or Chinese wagons comes on European ground...

Who takes care the traffics?

There are a large number of companies providing transport offers between China and Europe, and vice versa. But these are subcontractors, like for example the Dutch New Silk Way Logistics. A distinction must also be made between the choice of the train operator, the owner of the wagons and the owner of the containers. For reasons of cargo safety, i.e theft, marine containers are the only intermodal transport units proposed. For your information, here are two companies offering services in Asia:

- Far East Land Bridge Ltd. is a public operator which provides transportation of containers via the European, Trans-Siberian, and Chinese railway network. The company was founded in 2007 and is based in Vienna, Austria with additional offices in Cyprus, Germany, Italy, Russia, and China. As of September 30, 2014, Far East Land Bridge Ltd. operates as a subsidiary of JSC Russian Railways Logistics.

- Trans Eurasia Logistics GmbH (TEL) is a joint venture founded in March 2008 by DB Mobility Logistics (40%), Rossijskije Schelesnyje Dorogi (russian railways RŽD, 30%), TransContainer (20%) and Kombiverkehr (10 %).

- YXE International Container Train has been operating regularly between Yiwu and Duisburg since 2014 and its new branch, Yixinou International Freight GmbH, is a point of contact for logistics companies based in Duisburg and other local industries.

- Far East Land Bridge Ltd. is a public operator which provides transportation of containers via the European, Trans-Siberian, and Chinese railway network. The company was founded in 2007 and is based in Vienna, Austria with additional offices in Cyprus, Germany, Italy, Russia, and China. As of September 30, 2014, Far East Land Bridge Ltd. operates as a subsidiary of JSC Russian Railways Logistics.

- Trans Eurasia Logistics GmbH (TEL) is a joint venture founded in March 2008 by DB Mobility Logistics (40%), Rossijskije Schelesnyje Dorogi (russian railways RŽD, 30%), TransContainer (20%) and Kombiverkehr (10 %).

- YXE International Container Train has been operating regularly between Yiwu and Duisburg since 2014 and its new branch, Yixinou International Freight GmbH, is a point of contact for logistics companies based in Duisburg and other local industries.

Customs documents

A major difficulty is paperwork, especially on such destinations. Poor writing can block a container at transhipment points and lengthen travel times. In concrete terms, the contractual bases for international rail transport are covered by the "Uniform Rules concerning the Contract of International Carriage of Goods by Rail" (CIM). All rail transport must be covered by a standard consignment note. This document applies in the full area covered by the Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail (COTIF). This has included Europe, the Maghreb and the Middle East for years, but not still China. Recently, the functional and technical requirements of this letter were finalized in January 2017 with the creation of Raildata, an IT platform that is only used for the moment for the flow of information between companies. Significant improvements are being finalized for the transit at Khorgos or elsewhere.

The chargeable weight a container approximately loaded with 9,6 tons by rail transit, cost $8000 by comparison to $3000 on ocean freight. On air freight, charges would soar to $30,000 for a same loading. It is thus conclusive to say that rail transit averages the two: offering a cut down on air freight service prices while also cutting down on transportation time from the maritime route.

The chargeable weight a container approximately loaded with 9,6 tons by rail transit, cost $8000 by comparison to $3000 on ocean freight. On air freight, charges would soar to $30,000 for a same loading. It is thus conclusive to say that rail transit averages the two: offering a cut down on air freight service prices while also cutting down on transportation time from the maritime route.

Trains traffic

According to China Railway Corporation, 2,497 freight trains ran during the first six months of 2018, up 69% year on year, with growth on target to reach 5,000 trains by year-end.

First train Chongqing - Duisbourg in spring 2014. The diesel locomotive indicates that electrification stops more far. Containers change of train at the Sino-Kazakh border (photo cn.news)

In May 2018, it appeared that the Sino-Kazakh border points of Alashankou and the Polish-Belarusian Malaszewicze were congested. The containers on the train have to be unloaded and change wagons due to gauge and customs procedures. As most trains pass through these border points, containers are stalled for three to four days. It was necessary to find other outings of Russia. This was notably the case of Dzerzhinskaya-Novaya Kaliningradskaya, a terminal in the south of Kaliningrad, a Russian enclave with Russian railway network gauge which has a standard European railway line gauge line. In spring 2018, the trade press showed the simultaneous change of two trains: a Duisburg-Chongking and Chongking-Duisburg exchanged their respective containers directly (photo).

Alashankou, the Sino-Kazakh border

Terminal of Kaliningrad, between russian territory in Baltica and Poland.

On the other side of Russia, an alternative on the road to Kazakhstan is to go through a second border point, the border crossing of Khorgos, near the Chinese city of Khorgas. A 293-kilometre railway was completed from the Khorgos border crossing to Kazakhstan’s Zhetygen terminal end 2011, and the tracks from the Chinese and Kazakh sides of the borders were connected one year later. Today, more than fifty trains already cross through Khorgos Gateway every month. The speed of development at Khorgos has been remarkable. Khorgos is an emerging site situated across the eastern reaches of the Saryesik-Atyrau Desert, extends across the border between Kazakhstan and China. It is formed of a cross-border free trade zone, a dry port, a 450-hectare special economic zone and a new city. Companies such as HP and Foxconn are taking advantage of the Silk road railway to transport their high-value products to Europe with more speed, using the multiple trains which now depart Khorgos daily. From there, the journey continues on wagons at the Russian gauge of 1.520mm to Malaszewicze, on the Polish border.

Duisburg, first destination in Europe

Every week, around 25 Chinese trains pass through the rail terminal in Duisburg, Germany, laden with consumer goods from cities like electronics hub Chongqing or Yiwu, where an estimated two-thirds of the world’s Christmas decorations are made. The city is host to the world’s largest inland port, with 80% of trains from China now making it their first European stop. In 2013, only 3 container trains a week travelled between Chongqing, Kazakhstan and the European logistics hub of Duisburg.

The China connection kicked off in earnest in 2011 with Hewlett Packard commissioning a service to shift its laptops to Europe from Chongqing. Trains also come from Yiwu, the global bazaar of low-end Chinese products. But it was also necessary not to send empty trains to China. On the way back, Chinese containers are filled with luxury German cars, Scottish whiskey, French wines and Milan textiles destined for the Chinese market.

Congestion problems in Poland could guide freight forwarders to other transhipment points, such as those with Finland, the Baltic countries or below, in Slovakia via Ukrainia. There should be other Duisburgs in Europe. For the moment, the German river port is maintaining its lead thanks to its location in the middle of Europe, in one of the richest areas of the world.

Every week, around 25 Chinese trains pass through the rail terminal in Duisburg, Germany, laden with consumer goods from cities like electronics hub Chongqing or Yiwu, where an estimated two-thirds of the world’s Christmas decorations are made. The city is host to the world’s largest inland port, with 80% of trains from China now making it their first European stop. In 2013, only 3 container trains a week travelled between Chongqing, Kazakhstan and the European logistics hub of Duisburg.

The China connection kicked off in earnest in 2011 with Hewlett Packard commissioning a service to shift its laptops to Europe from Chongqing. Trains also come from Yiwu, the global bazaar of low-end Chinese products. But it was also necessary not to send empty trains to China. On the way back, Chinese containers are filled with luxury German cars, Scottish whiskey, French wines and Milan textiles destined for the Chinese market.

Congestion problems in Poland could guide freight forwarders to other transhipment points, such as those with Finland, the Baltic countries or below, in Slovakia via Ukrainia. There should be other Duisburgs in Europe. For the moment, the German river port is maintaining its lead thanks to its location in the middle of Europe, in one of the richest areas of the world.

Everyone wants his Chinese train

In recent years, there were more announcements in the medias about "first Chinese train arriving at ...". Each european city must be linked at the chinese route. This should surprise the Chinese themselves, very happy of the interest in "their" OBOR ...

In recent years, there were more announcements in the medias about "first Chinese train arriving at ...". Each european city must be linked at the chinese route. This should surprise the Chinese themselves, very happy of the interest in "their" OBOR ...

Chengdu-Tilburg (NL) (photo Rob Dammers via flickr)

Yiwu-Madrid, with spanish gauge... (photo Shangaï Daily)

To export: London -Yiwu... (photo News CN)

Tangshan-Antwerp... (photo News CN)

Harbors and TEN-T corridors

If the railway part of the OBOR is the "belt", the maritime part is the "road". Contrary to what one might think, to talk about the OBOR ports in Europe is also talking about the railways. The Chinese are taking a great interest in the Mediterranean sea and Suez because they are becoming more important vis-à-vis serving the US east coast, which can possibly be done better from there than via Panama. This is not just about transport investment, but should also be seen in the context geopolitics and strategic objectives.

The two European ports Chinese authorities were focusing on were Piraeus, where Chinese terminal operator Cosco Pacific now has the concession to manage container operations, and more curious Venice (instead of Trieste).

The two European ports Chinese authorities were focusing on were Piraeus, where Chinese terminal operator Cosco Pacific now has the concession to manage container operations, and more curious Venice (instead of Trieste).

Venice is considered as important because it has good rail connections with North Europe as well as a proximity to the logistics parks in the north of Italy. In Venice, chinese are looking at developing a €1bn offshore container terminal designed by Royal Haskoning. The Chinese have said that they would fund €750m of this if the Italian government funds the remaining 25%.

New harbour project outside Venice...

It must be kept in mind, however, that a lot of the Chinese terminal operators are acting as an arm of the Chinese government, so it really is a case of geopolitics acting in concert with supply chains. With this strategy on two European ports, one question is to know how does this investment align with the EEU’s TEN-T programme. EU policies are primarily internal, about linking the continent’s transport networks, whereas for the Chinese, it is about entry points on a wider market. The impact on rail traffic and the great interest of the four tunnels planned under the Alps are being measured here, two of which are already in service in Switzerland.

Trade deficit

So far the Silk Road has garnered a lot of publicity, but the business case isn’t yet certain. Some experts said there was growing concern that the new Silk Road might become a one-way gateway to flood Europe with China-made goods. Getting enough cargo moving toward China is a persistent problem, which is very well known in the maritime sector, which carries many empty containers on its vessels to China.Before 2012, the rail line moved four times more Chinese goods to Europe than went the other way. That’s since been cut to a two-to-one deficit, as high-value consumer goods like French wines, Scotch whisky and Italian textiles head east to sate China’s burgeoning middle class. But that's remains insufficient.

Trade must do not a one-way game, and in order for the rail link to make commercial sense it has to work in both directions. This requires that industry and European officials accentuate their positions and efforts for growth. The OBOR concept must be to follow with attention.

Trade must do not a one-way game, and in order for the rail link to make commercial sense it has to work in both directions. This requires that industry and European officials accentuate their positions and efforts for growth. The OBOR concept must be to follow with attention.

-WEc780af7f81.png)